Navigation

This chapter presents basic navigation techniques. Some comfort with basic arithmatic, geometry, and trigonometry is required. Separate chapters discuss locating yourself using survey markers and GPS.

Depending on the trail, navigation for Long Distance Hikers can be very simple or quite complex.

The Appalachian Trail is among the simpler trails to follow. For the most part, the trail tread is well worn into the soil. There are white paint blazes on trees marking the AT quite frequently. Side trails, and other land marks often have signs with names. There are several competing guidebooks and maps which tell you that the shelter or town you're heading for is so many miles from the signed trail intersection you're at. And if that isn't simple enough, there are plenty of people to ask for directions and advice.

Junction with Trail # 37E01

At the more difficult end of the spectrum are, for example, the Grand Enchantment Trail and the Hayduke Trail. These are not actually trails at all, but rather routes that are sometimes on trails or roads, and sometimes cross country. Getting lost would be much easier, and being lost might make finding water impossible or lead you through dangerous terrain. So a failure to navigate properly could well be deadly.

The Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail fall in between. There is usually a well defined trailbed, but blazes and signs are infrequent. There are critical water sources to find, and miles long patches of snow or ill defined tread in a few places require cross country navigation skills.

It's very important to hike on a trail for which your navigation skills are adequate. But if you aspire to hike on tougher trails, while hiking easier trails you can hone your navigation skills...

Acquiring Navigation Skills

Let's say you hike the Appalachian Trail in a group. You never look at the guidebook or maps. You do whatever your friends suggest and question nothing. It's entirely possible you could finish your 2100 mile hike with very strong legs and almost no knowledge of navigation. And because of that, you're not ready to move on to the PCT, CDT, etcetera.

The hiker discussed in the preceding paragraph is doing something dangerous and stupid. On a months long hike, it's easy to get separated from your partners, and it's easy to get off the trail. Learning to navigate and always knowing where you are both critical to safe long distance hiking. Counting on others to always help you is irresponsible and does not always work. There are many cases where navigation errors can kill you.

On the other hand, let's say on your AT hike you actually carry topo maps instead of some data book that tells you almost nothing about the land around the trail. Each night, you study the topo maps for the next day's hike and use them to predict where there will be water sources, where the trail will be steep, and where there will be great views. The next day, you check your predictions and see whether they were correct. If not, you figure out why not. You study every symbol and nuance on the map, and are relentless about chasing down their meanings and relating them to your experiences. By the end of your hike, you will have learned quite a bit about maps, terrain, and navigation. And if you take this approach with all aspects of navigation, you can learn quite a bit, even though the AT is not particularly difficult to navigate. The same approach can be taken on any trail near your home, and classes are also available.

So let's discuss some of the navigation skills long distance hikers use.

Reckoning

Dead Reckoning (sometimes spelled ded, or deduced) is a term derived from old time sailing. In the old days of sailing across the Mediterranean Sea, captains would wait until winds were blowing in the direction they wanted to travel. The boats had little ability to sail away from the direction the wind was blowing. So they knew they would sail exactly in the direction the wind was blowing. And they knew how hard the wind was blowing. Based on personal experience, knowledge passed from one captain to another, and Portolan Charts, they knew if they left a certain port in a certain direction, they would end up in a certain place on the other side of the sea. And by knowing how hard the wind was blowing, they knew how fast they would go, and therefore how long it would take to cross the sea.

Under very rare circumstances, a hiker may travel cross country, let's say across flat, unvegetated land, in a particular compass direction. Experienced hikers know their approximate speed. So they can know how far they've walked by keeping track of time. And if they knew where they were in the first place, and they know how far they went and in what direction, they still know where they are. In this case, hikers are dead reckoning.

Keep in mind that since we don't know exactly how fast we walk, and we may err a little in our direction, there is a little uncertainty as to our position created with each dead reckoned segment. Hopefully, after one or a few dead reckoned segments, we use some other method and nail down our exact position.

Hikers almost never travel in a straight line. We follow trails that wiggle around rather than going straight. Still, if we have a book or map that tells us that the on trail distance from where we are to some lake we want to get to is 3½ miles, and we know we walk about 3 miles per hour, then we know it should take about 70 minutes to walk there. If we come to a lake in 20 minutes, it's either not our lake, we didn't know where we were in the first place, we walked at a very fast pace, or the map was wrong. This technique is known as reckoning. It's not dead reckoning because we changed direction on the wiggling trail.

Ambiguity in Navigation

It's not particularly rare to be uncertain of your location as in the previous example. Maps and guidebooks are not perfect, and they might not show the pond you found in 20 minutes. The sign that told you where you were in the first place might be wrong. Or you may be on the wrong trail.

Because a single navigational clue may be wrong, or may give you inadequate information, experienced hikers gather clues all day. They rate the clues for how strongly they indicate position. And they combine the weaker and stronger clues into a bigger picture.

Comparing Topo Maps to Land Features

A topo map has lines which indicate elevation or altitude. If the lines are very close together, the terrain is very steep, and conversely, the land is fairly flat where the lines are well separated. Hikers need to study topo maps until the shapes of mountains, canyons, holes, cliffs, and etcetera pop out at them, and they can recognize the shape of the terrain before them in the topo line on the map.

A topo map may show a lake with a unique long, skinny shape, or it may terminate at a cliff. If you can recognize that lake from your viewpoint, and correlate it to your map, you have a clue as to your position.

Marie Lake's islands make finding it on the map easy.

Topo maps may also show shapes of trails, roads, rivers, etcetera. Treelines may be shown, or large mines. Good navigators stop at viewpoints and try to correlate as many mapped features as possible to the actual terrain. It's impossible to know what observation may come in handy later. So from a viewpoint, many navigational clues in the distance can be pondered.

There are also certain point each day when you know exactly where you are. Let's say you're only crossing one pass today. When you summit the pass and see the trail rolling down the other side, you know your position. Often, I write down the time on my map so that later I'll know when I was there. Later, I'll use that as a clue in reckoning my position. I may also know my position because I'm crossing the only creek with a bridge, or passing the only mine with a big yellow tailing pile, or the third road, or whatever. If the clue is unique enough, I know where I am and I'll note the time on the map.

Sometimes there is a sign which tells me exactly where I am and that make things very easy. But don't forget that signs may be wrong or misleading. For example, roads in national forests often have multiple numbers and names. If you find a road sign with a number or name that does not match those on your map, it still may be the same road. If it's important, see if the road has the same curves, passes the same ponds, etcetera.

Topo maps are often based on information that is 50 or more years old. A building shown on a map may now be nothing but a shallow hole where the cellar was, or a couple of rotten logs. Or nothing may be left. Often, the trail you are on may have moved since the map was made, or the map may show no trail at all since the trail is less than 50 years old. The map may show a trail that no longer exists. If a slope burned, and logs and mud covered the trail, and weeds and bushes grew over it, then maybe no one tried to follow it or fix it and it's just gone. So hikers need to understand that even a newly printed map may have out of date information.

Sometimes maps or guidebooks show trail distances. If they don't, and we need distances to reckon our progress along the trail, then we need to estimate them. Topo maps usually have a scale bar which shows a nice, straight mile, or whatever. And then they have a bunch of wiggly trails. You can carefully measure the trails by swinging a ruler along the wiggles, or using a map wheel. But usually, the more wiggly a trail is, the less accurate its representation on the map is. So a super accurate measurement of the line is not really much more valuable than an eyeball estimate. Many topo maps have some sort of grid imposed over the map. The squares may or may not be a mile, so you may need to multiply to convert grid squares to miles or whatever. You can count how many squares the trail crosses. If the trail appears quite straight, it may be 10-20% longer than the length of the side of the squares. If there are a lot of switchbacks or other wiggles, the trail may be 3 or 4 times as long as the square it crosses. With a great deal of map and trail reading experience, you can make a surprisingly accurate guess as to the length of the trail. You can also fudge in a little extra time for very steep terrain, or for bottomlands if you've noticed they are extra brushy, or whatever. Reckoning like this takes practice. Only those who spend the time to navigate and understand the daily patterns while they are still found will find navigation easy when they become lost.

Following a Trail

It's not too difficult to follow a trail when we can see a well defined dirt groove in a forest floor otherwise covered in leaves, or when there are plenty of blazes or signs. But there are tricks to following trails when they are less obvious due to overgrowth, snow, etcetera.

Axe or Bark Blaze

Let's say you're walking down a popular trail like the Pacific Crest or Appalachian Trails. Normally these trails are maintained and used in a uniform way. Let's say you've been walking down a typical groove in the dirt but now you've come to a place where the trail crosses bedrock. There is no deep groove. Because many other people have walked down the trail, the trail appears different than the bedrock to either side. Moss and lichens grow off to the side, but are worn off on the trail. Gravel and mud is tracked along the trailbed, so some gravel and mud color sets the trail apart from undisturbed rock. Bushes are trimmed back, and sticks and logs are removed from the trail corridor. To step off the trail, you would have to bushwhack and step over sticks more than you have been earlier in the day. However frequently there were blazes earlier, there should be blazes now. If there were bits of trash and fibers and lint from hikers' clothes, they should still be present. If there are thick woods, a clear tunnel envelops the trail. Noticing norms like these is key to staying found.

Trails have both short and long term usage patterns. If you're walking down the PCT or AT in the middle of through hiking season, there will be a certain density of boot prints in the soil of the trailbed. If you now come to a branch in the trail, and one has hardly any prints compared to the average, while the other is average, chances are the one with few prints is a side trail. A side trail with many footprints may go to a popular trailhead. Chances are, people arriving at the intersection will mill around while waiting for friends and deciding which way to go. This will create a large beaten area and footprints in random directions, very unlike a typical section of trail. So by merely observing the quantities and qualities of boot prints, you can distinguish little used side trails from heavily used side trails and from the main trail.

The same thing can also be done by observing trail maintenance. If the main trail has a nice, flat trailbed, and the bushes are trimmed back, and one branch has a big rain rut and overgrowth, that's probably not the main trail.

If you're walking down the trail in the dark and you would rather not use your light, you may be able to feel the flat part in the middle of the trail groove. If you feel the soil sloping up, maybe you're walking out of the groove. If you've been feeling dirt and stones under your feet in the trailbed, and now you feel leaves, pine needles, or a cushy duff layer, you're off course. If the trail has been well brushed, but you run into a bush, perhaps it's time to turn the light on and see where you screwed up. Human beings are well adapted and prefer to use sight, but there are many non-visual clues in navigation.

Let's say the trail has been little used and is now somewhat overgrown with weeds and bushes. The trail bed groove may still be present. If the soil was very compacted, maybe plants don't grow as densely in it as off to the side. If it traps water, maybe weeds grow more densely. Either way, a visual clue is present. A properly installed blaze points straight down the trail. If the trailbed vanishes for a few tens of yards, walking out in the direction the blaze indicates may help locate the trail. Though bushes and weeds may have overgrown the trail, tree branches sawed off long ago may still show as scars along the trail, and a clear tunnel through tree branches may still be visible. Ancient blowdowns may still be cut to allow passage on the trailbed you can no longer see. Occasional lengths of clear trailbed reinforce all these other clues as you navigate this long abandoned trail.

Let's say the trail has been little used and is now somewhat overgrown with weeds and bushes. The trail bed groove may still be present. If the soil was very compacted, maybe plants don't grow as densely in it as off to the side. If it traps water, maybe weeds grow more densely. Either way, a visual clue is present. A properly installed blaze points straight down the trail. If the trailbed vanishes for a few tens of yards, walking out in the direction the blaze indicates may help locate the trail. Though bushes and weeds may have overgrown the trail, tree branches sawed off long ago may still show as scars along the trail, and a clear tunnel through tree branches may still be visible. Ancient blowdowns may still be cut to allow passage on the trailbed you can no longer see. Occasional lengths of clear trailbed reinforce all these other clues as you navigate this long abandoned trail.

If the old trail becomes completely impassable for a ways, perhaps you can examine the map. Maybe the trail will certainly go to a lake ahead, or through a very restricted canyon. If so, perhaps now you can go cross country a ways and pick up the trail after its completely blocked section.

What if the trail is covered in five feet of snow? Old blazes, and the branch scars and tunnel discussed above may be visible. In the woods, the surface of the snow often sags over the trail. The trailbed is bare dirt, and heat from the soil rises and melts the snow layer a little. To the side of the trail, leaf duff covers the dirt and insulates the snow from the heat in the soil. The snow to the side of the trail melts a little less. The faint sag may be more visible in the early morning or late evening when light from the side casts shadows in the shallow sag over the trail. Sometimes, if you follow the few blazes, scars, tunnels, and sag clues, you will find a few places where the snow has melted through and gives you the ultimate clue, seeing a few feet of the trailbed.

Finding Water

On the western US long distance trails, finding water often requires attention to navigation. A guidebook may say "Walk down a long abandoned logging road a quarter mile to find the only reliable spring in the next 8 miles." What it doesn't say is that there are 47 other abandoned logging roads in the area. It will take 10 minutes to walk down and up each logging road you try, so picking the right road is important.

In arid areas, those few places with a lot of water often look quite different. Plants growing away from water are whiter and more drab. Plants growing in the wet area near water sources may be darker, greener, shinier, or more vibrant. Bushes and trees are taller near water, and certain species grow only near water. Wet soil is usually darker than dry. You may see birds flying to and from water sources more than to other areas. Large mammals may congregate there. These clues are all specific to the area. If at every water source, you observe the surroundings, and see how the watered area differs from its surroundings, later you may infer water sources that few others know about.

Often, you may hear water trickling or more birds chirping at water.

Certain plants grow only near water, and some fungus may thrive in wet soil. If these have unique scents, you may be able to smell water sources. Again, only by noticing the smells of previous local water sources will you know what to sniff for.

Sometimes, the side trail clues discussed above will help you find water. A well beaten side trail may go to water. Parties often rest at an intersection and send one or two members down for water, or people leave their packs at the junction. So the junctions have large beaten areas and many footprints. Many people will camp only near water, so if you find developed campsites in an arid area, look around for clues to water.

In some areas of the west, there are no natural water sources for days, and hikers get their water from sources developed for cattle ranching. In these cases, you're looking for troughs, tires, pipes, hoses, tanks, windmills, and solar panels. Even if you find these, there may be no water. Cattle are often moved to desert regions for winter, and mountain regions for summer grazing. Sources are turned off when the cattle leave. And some water systems may be long abandoned. Use some of the clues discussed above for finding natural water sources to try to guess which systems hold water. Any congregation of cattle is almost certainly near water. Topo maps often show tanks, windmills and wells. Even though the information may be 50 years out of date, some of these sites still have water.

All of these water sources are maintained by ranchers on a very thin budget. Make sure you break nothing, and get your water and leave as soon as possible so the cows will feel comfortable coming to drink. Don't camp or rest at artificial water sources. Some ranchers will be offended if you wash or swim in the source, so if it's necessary, carry some water ¼ mile away and wash there. If a rancher decides to quit maintaining a water source near a trail, future hikers will be out of luck.

Choosing Compasses

Complex Compasses

There are some very nice compasses available at outdoors retailers. They have features like declination adjustment, rotating protractors, inclinometers, sighting mirrors, magnifying glasses, millimeter and inch rulers, distance scales for popular map series, etcetera. There is a sport called orienteering, in which people try to learn to use every feature of these compasses, and use them to navigate extremely precisely from one known point to another. If you're an orienteer, or a surveyor, forester, geologist, etcetera, you may well want to start at one marker, and very precisely walk in a certain direction for a certain distance, and know you're within a foot of another marker. Compasses with these features, and perhaps more, are necessary. Professional compasses have all these features, are built to be used more precisely than compasses from outdoor stores, are more ruggedly built, weigh more, and are more costly.

Simple Compasses

Usually, if a long distance hiker is within 100 yards of where he wants to be, he can see his destination. In fact, in a 28,000 mile hiking career, only once did I need to be within 5 feet to see a water source. So a compass 100 times less accurate does the job well enough almost every time. Simpler compasses can be easier and faster to use, and cheaper, lighter, and more rugged than compasses with a lot of gadgets.

Different hikers prefer simple or complex compasses.

Tilt in the Earth's Magnetic Field

The magnetic needle in a compass lines up with the magnetic field around it. The magnetic field is not always level: sometimes it tilts down towards the earth. When you hold out a compass and try to read the direction, it may be necessary to try tilting the compass in various directions until, by wiggling the compass, you can see that the needle wiggles freely and then settles in a direction rather than sticking in certain directions and moving only when you wiggle the compass. In the field, when it's cold, wet, windy, slippery, and etcetera, it can be frustrating to stand around and try to get the position just right time after time.

Many compasses, including most of the fancy compasses at outdoor retailers, work with only a very specific amount and direction of tilt. If you want a compass that turns freely without a lot of care, you'll have to test the various compasses at the store to find one.

In some countries, notably in the south Pacific in and near Australia and New Zealand, the inclination is so steep that compasses are made with a needle which is a little heavier on one end than on the other. Because of this, the compass can be used level even though the magnetic field is tilted. These compasses are sold as Zone 5 compasses. Some of the better compasses sold for these regions can be opened and a small weight slid along the needle for balance.

Compass Protractors

It's nice to have a compass that has all 360° marked on the protractor around it. But smaller compasses don't have enough space to make these graduations readable. If you can interpolate accurately between whatever marks the compass has, then it's good enough. If you're mathematically challenged, maybe you want the full protractor.

Using Compasses

Magnetic Anomalies

Unfortuneatly, magnetic compasses don't always point north. Sometimes, where iron is part of the dirt in an area, the compass points towards this ore body rather than the north pole. And as you walk around the ore body, the offset from north keeps changing. The only practical way for a long distance hiker to know that the compass doesn't work locally is to occasionally use it when she knows where she is. If, from a known position, you can see a known peak, and you know its direction is 32°, and the compass reads something entirely different, then you know there is a local magnetic anomaly. A little later, when you're lost, you can discount your trust in the compass reading accordingly.

Any bit of iron or electronic device you are carrying can also locally change the direction of the magnetic field. Be aware of your own personal magnetic field by passing your compass over your poles, stove, GPS, wristwatch, etcetera. If the compass direction changes as you approach some bit of gear, you will need to take your readings away from that equipment. You might have to walk a few feet away from your pack. I have found that some of my wrist watches affect the compass reading, so I hold my compass in the other hand and keep the watch away.

Declination

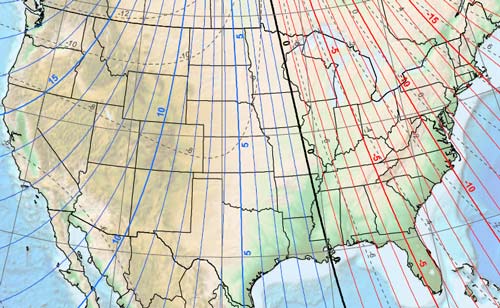

On most maps, true north is straight up. Any grids on the map are true east-west and north-south. But needles on magnetic compasses don't point true north. Whether you have a fancy compass with a declination adjustment, or a simple one, you must compensate for declination. Many people, when given a declination of, say, 11° West, get confused as to which way to make the correction. And a 22° error would cause horrible navigation problems. So practicing until you understand is critical. Many topo maps have a diagram that shows the angular differences between true north and magnetic north (declination) which people find easier to understand. As an added bonus, the diagram often also shows the direction to Polaris, the north star, in case you're navigating that way.

Magnetic Declination Map, NOAA, 2010

Red is Negative or West Declination

Blue is Positive or East Declination

Finding Yourself on a Trail

Let's say you're walking along a fairly featureless section of trail and you want to know where you are. Off to the side of the trail, you can see a mountain that you can also see on your map. You get out your compass, and take a reading to the mountain. Now, you set your compass on your map over the mountain, and use it as a protractor. You can eyeball where you are on the trail. Or, if you want a straightedge and you're too lazy to carry one, you can use a pine needle or a stalk of grass to lay the line across the map.

Finding Yourself Off Trail

In the previous example, we found our location at the intersection of two lines, the trail and the direction from a peak. But a lake, tower, or any other recognizable location would work as well. A minimum of two lines is required to find your location using just a map and compass. The location is most accurately found using two lines at close to a right angle. That's why we chose a peak off to the side of the trail to sight. In the middle of nowhere, we sight two peaks, etcetera, near 90° apart, and lay both lines on the map. The intersection is our location.

Since we may have made errors laying the lines in, or identifying the peaks, making three or more sightings and ensuring they all intersect at the same place is a good idea.

Dead Reckoning

In another common use of compasses, maybe you've reached a point in the trail where you're supposed to travel cross country in a certain direction for a certain distance to find another trail segment, water, etcetera. (Dead Reckoning... Yeehaw!) You take out your compass and find the direction in which you need to travel. As you pass around bushes, rocks, etcetera, you keep changing directions. Just looking at the compass all the time doesn't really keep you on course. And if you're staring at the compass, you'll trip over rocks, etcetera. So instead, you find the most distant object you can see near the direction you need to travel. In a forest, maybe it's a tree 30 yards away. Out in the open, maybe it's a big rock on the horizon. Usually, the most unique looking objects are not quite in the direction we need to go. So we figure out, say, how far to the left of the object we're aiming for, and walk in that direction. Occasionally, we check with the compass and see that we're still on track. Or, in the forest, we sight a new object each time we reach the old one.

Let's say there's no unique looking object ahead of us. With a little more trouble turning around, we can walk straight away from an object. And checking occasionally with the compass, if we've drifted to the side of the direction we're trying to follow, we can use the compass to return to the center of our course.

If there is a distant object to our side, we can walk so that object is always at the same angle. Maybe it's ten degrees in front of our left shoulder. So long as the obect is distant, and we walk maintaining the same angle, we're traveling in the same direction. However, if the object is close, this method will have us walk a curved line.

Navigating by the Sun

The sun is particularly useful using this method. Even in a forest where you may not be able to see far, on a clear day you may see the sun and its shadows. Obviously, the sun moves across the sky, so you need to reorient periodically with your compass. But it's quite easy to walk 30° to the right of the sun, or straight in line with the shadows, etcetera.

So there are many ways to dead reckon without constantly looking at your compass.

Navigating by the North Star

On a clear night, it may be easiest to navigate by the North Star, Polaris. Its direction is very close to true north, so if you can see Polaris you can easily estimate the direction you're travelling.

Finding the North Star

Polaris, or the North Star, is White

Red is the Big Dipper or Ursa Major

Green is the Little Dipper or Ursa Minor

Blue is Cassiopeia

You can find Polaris on winter evenings and summer mornings by Cassiopeia, or by Ursa Major and Minor, The Big and Little Dippers, on summer evenings and winter mornings. They further north you are, the more likely you are to see all 3 at once. Personally, I can see the dippers, but the idea that they look like bears, or that Cassiopeia looks like a woman makes no sense to me. What I can remember is that Polaris is the end of the handle of the Little Dipper. Or that the two stars of the side of the cup opposite the handle of the Big Dipper, Merak and Dubhe, point straight to Polaris, and the distance to Polaris is several times the distance between Merak and Dubhe. Or that Polaris and Cassiopeia together look like an arrow with a broken and bent arrowhead, with Polaris where the arrow attaches to the bowstring. Whatever works for you...

Rulers

If you need a ruler to measure a distance on a map, but don't have one, a straight stalk of grass or a pine needle can substitute. I like them to be dry. I lay it along the scale or on the map feature I want to measure, pinch it off with my fingernails to the length I want to measure, and transfer it over to whatever I'm comparing it to. A straight edge of the exact length I want is almost always available!

Conclusions

First, all of these methods require practice to learn. And many of them require that you observe constantly while you're found if you're to know what to do when you're lost.

Second, if you're mathematically challenged, you'll have to work that much harder to use maps and compasses.

Using survey markers and GPS for navigation are covered in the following chapters.